How often have we heard someone say people only had one or two changings of clothing during the 18th century? There are a great many factors that determined this in each family just as there are several ways of seeing exactly what sort of clothing someone had.

A perusal of estate inventories will show exactly what someone owned when they died, at least what they owned that was in good enough condition to sell.

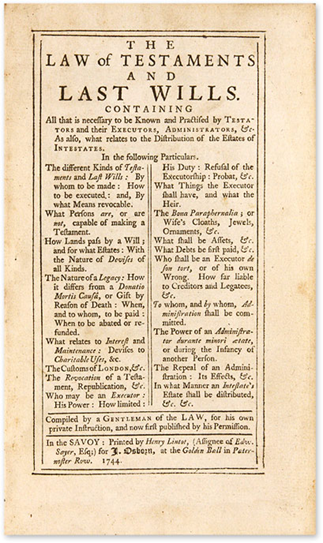

An estate inventory is a legal accounting of anything of value owned by an individual at the time of their death, and given there was a huge market for used clothing in Europe and the colonies articles of clothing could be sold along with livestock, household goods (bed linens, pots, pans, candle sticks, furniture, crockery, etc.), farm implements, tools, food supplies on hand (bushels of grain or produce, salted/smoked meat, molasses, pickled herrings), lumber, fabric, books, etc. Only rarely did this include every day work clothing the condition of which made it of value only to the rag buyer.

There is a difference in patched and well-worn work clothes and average “every day” clothes. In examining an estate inventory from NC, 1753 we find an old mantle (cloak or shawl), old woolen jacket, 5 homespun petticoats, a cotton jacket, 2 pairs of stockings, a quilted petticoat, 3 homespun petticoats (probably of a different fabric to be listed separately), 2 shifts, 6 aprons, 4 “fine” caps, a checked handkerchief, a half yard of homespun, a pair of pockets, a single pocket, a hat, basket, and pair of gloves.

When Mary Wickham died in 1705 the following articles of clothing were enumerated: 4 petticoats, 2 gowns, 7 hoods, 11 handkerchiefs, 6 aprons, 10 caps, 4 cornetts, 2 pair sleeves, 1 neckcloth, 1 pair of bodyes (stays), 1 pair of stockings, 3 hoods, 2 shifts, 2 waistcoats, and 2 pairs of women’s gloves.

An estate inventory from 1770 in NC listed two bonnets, one white and one black. We can sometimes compare articles of clothing with myths about the age of women who wore various garments. Example: the myth that only young women wore short gowns is debunked by the inventory of an unmarried woman approaching 50 dying in the 1770s with short gowns listed in her estate inventory. The same inventory proves that short gowns were worn outside of Pennsylvania, despite some previously expressed thoughts to the contrary, and that gowns were often of brilliant colors – in this case crimson silk and purple and white chintz.

Another from 1755: 1 pair of stays, 1 silk gown, 1 chintz gown in black and white, 1 calico gown, 1 striped gown, stockings, 1 skirt, 1 cloak, a velvet hood, a muslin (fine sheer cotton) apron, 3 shifts, 2 handkerchiefs, caps, and an apron.

The estate inventory of Andreas Hagenbuch, PA, 1785 listed 2 hats, a brown coat and a blue jacket without sleeves (waistcoat), a brown jacket and a white jacket without sleeves, two jackets (unspecified), a greatcoat, 2 pairs of deerskin breeches, a linen jacket, linen drawers, four shirts, four new shirts, stockings, two pairs of shoes, and a great deal of linen fabric, in varying grades (almost 60 yards), mittens, and 3 caps.

On the more elaborate end of the scale, we see Mary Cooley’s [1778, Williamsburg] clothing consisted of: 1 Brown damask Gown, 1 black Callimanco Gown, 1 Striped Holland Gown, 1 dark ground Callico, 1 Callico Do, 1 flower’d Do, 1 India brown Persian Do, 1 Purple Do,1 flower’d Crimson Sattin Do.,

1 Cotton Wrapper, 1 Striped holland Gown, 8 pair Stockings,4 Pocket Handkerchiefs,

2 single Handkerchiefs,6 double Do, 15 Caps, 4 Aprons, 1 Sattin Cloak1, 1 Sattin Hat, 1 Fan,

1 black Shalloon Petticoat, 1 blue Callimanco (fabric made of worsted, long fibers of wool, it came in a wide array of patterns, stripes, floral, etc., and brilliant colors) petticoat , 1 India Cotton Petticoat, 1 pair Stays , blue Quilted Petticoat, 4 pr. Leather Shoes, 1 pr. black Sattin Shoes, Parcel Stone blue, Parcel Tape, parcel Thread, 2 black Laces, Parcel of Ribbon, 36 Needles & Case, Parcel Sewing Silk, paper Pins, and 1 pr. Silver buckles. [Do, aka Ditto, means Same].

Martha Jefferson, wife of Thomas Jefferson, not surprisingly left even more clothing including 16 gowns, two gowns to be made up, 9 petticoats, 18 aprons, and 20 shifts plus stockings, night caps, bonnets, shoes, handkerchiefs, pockets, etc. She was obviously able to afford what she wanted.

At this point, the reader should be asking if these are a small sample of what people had when they died, what were they purchasing in their lifetime and how much? The Diary of William Sample Alexander in the Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC at Chapel Hill is one of many documents which answers this question.

A 1770s, NC, shopping list entitled “Memorandum of things to fetch for the family [probably including extended family]” lists the following clothing items: blue Sagathy [light weight wool, sometimes wool and silk] for one suit of clothes, a piece of linen, pairs of silver buckles, 1 dozen linen handkerchiefs, white persian [thin plain silk] red lining and black tafety [taffeta] with trimmings (bonnets), a yard of cambric (fine white linen), half a yard of lawn (delicate linen used for shirts), 2 calf skins, check silk handkerchief, 2 pairs men’s stockings thread and cotton, 1 pair black silk mitts, red Durant (Durance, glazed worsted) for two petticoats, 9 yards pale blue calamanco, 2 ¼ yards of fine holland (good quality linen), 1 ladies Barcelona handkerchief black, 11 yards crape black and blue, 1 yard black ell wide persian, 3 yards black ferritin, 1 pair black gloves, 1 pair women’s shoes white or blue damask, one pattern for gown red and white calico, 2 silk handkerchiefs, 2 black 1 check, and light colored Sagathy for coat and jacket. Lawn and cambric fabrics in this quantity were probably for ladies’ caps or fichus.

I’ve heard that women had their gowns professionally made because they lacked the skills to make them at home. The amount of fabric purchased here and found in the above inventories indicates gowns and other clothing were being made at home. Perhaps the blog writer meant to say formal gowns weren’t made at home. A great many men and women had sewing skills enough to make their own clothing or to remake used clothing.

These are just a smattering of available estate inventories, and the reader may have one belonging to an ancestor for comparison. Good luck with your research and your sewing! Posts are copyrighted and may not be reproduced without permission. Thistledewbooks @ yahoo . com